I’ve long known that you could eat acorns. I just didn’t know how. I knew that Native Americans relied on acorns as a food source and that they somehow had a way to turn them into flour for little cakes.

I live in an area that has some oak trees, and eventually I became curious about how to actually utilize this resource. As you may know, there are numerous YouTube videos and chapters in books and website pages about processing acorns. The problem is, though, that once I started looking around, I found so much information I didn’t know what was reliable. There are many different ways that you can process acorns to make them edible. I wanted to know what really worked.

The resources I had also didn’t answer some basic questions such as whether it matters if the acorns are green or brown. One of the trees near me had acorns all over the ground, but they were all green. Does it matter if they have their caps on or not? I saw one resource on using acorns as a survival food that said acorn flour needed to be stored in the refrigerator or freezer. How will needing to keep the flour cold help me if I’m in a survival situation?

So when I saw that a group near me was offering a workshop on acorn processing, I immediately signed up. I was one of 10 students who spent most of a day with an instructor from a school of botanical studies (they teach herbalism and wild plant foods). We walked around an area with a lot of oak trees, learned to identify the different native species we have in my area (Oregon), and what the trees’ growth patterns can tell us about the environment. Regardless of what type of trees you have around you, all varieties of acorns are edible!

It’s fine to read books and watch videos, but if you have a chance to learn from a real instructor in person, that is highly preferable. You can ask questions, see, hear, smell and taste in a way that you never can by watching a video, no matter how detailed the instruction. Here’s what I learned about using acorns as a survival food. And to be honest, the acorn “mush” turned out so good that you might want to eat it all the time.

Our group walked around to learn how the trees grow. We learned that Douglas firs and other fast-growing trees compete with oaks for light, and if an oak doesn’t get enough sun over time it will die. Knowing what trees you might need to remove can help you manage oak trees if you want to make sure that the trees in your area stay healthy and keep producing. We also learned that oaks have some years where they just don’t produce much, and some years, called “mast” years, where the nuts are abundant.

Our instructor also reinforced the fact that native people had collected acorns from right where we were walking for thousands of years. It was a great feeling to know that we were learning how to keep this craft alive and that we were learning how to truly eat food on a local level.

After we walked around and talked, we collected our nuts. We learned to avoid acorns that still had their caps on. We picked up only brown acorns, avoided ones that had a hole in them which was due to an acorn weevil (more on that delicious little protein morsel later!) and we avoided ones that were cracked.

Then we got to work processing them. Our instructor let us spend a few minutes cracking fresh acorns before telling us that it would never work to turn fresh nuts into flour! So that’s survival lesson number one…if you want to use acorns as a survival food, plan ahead. They must be dried before you can pound them into flour. You can let them naturally dry over months, you can use an oven, or a dehydrator, or put them by a wood stove. But either way they can’t be used right when you collect them off the ground.

Here are some photos of the dried nuts she had pre-dried for us to use.

As you can see, the whole nuts that you use should be free of mold and yellow or green discoloration. The variation in color is ok as long as they are “clean” looking.

It takes about 20 minutes to pound about 1/2 cup of the nuts into flour using a mortar and pestle. If you use this method, pound, don’t grind. If you grind, you’ll release the oils, which will make it turn into nut butter. Maybe that’s what you want, but in this case we were going for finely ground flour.

If you have a meat grinder, that’s a much faster way to process the acorns. You’ll get some fine flour and some “chips” or “grits” size pieces. Those can be sifted out and finely ground by hand or cooked in a soup. You can also use a grain mill or some other technology if you have it available.

After you start processing your nuts, you’ll sooner or later find one of these acorn weevils. Go ahead and eat it! The little protein morsel tastes like nuts. It’s slightly sweet, and only a tiny bit chewy along the edges. If no one else in your group is willing to eat them, then good, that’s more protein for you. I ate one, and I lived to tell the tale.

After you collect the flour, it’s time to leach the tannins out of the nuts. The tannins are what make them bitter and you want to remove the tannins before you eat the nuts. There are many ways this can be done. One thing I was surprised to learn is that if you try to leach whole nuts (in the shell) it can take months. One person in the class had a brilliant idea of putting a bag of whole acorns into their toilet tank, so they were constantly being “flushed” through with fresh water. You can soak them in a large bucket. This takes months. Longer than you think. But the acorns are fine in the water for a long time. It’s better to store the whole nuts and process them into flour when you’re ready to use them rather than trying to store the flour. The flour won’t stay fresh for very long without freezing or refrigeration.

The smaller the acorn pieces, the faster they leach. We leached them in two methods…the first was to put the finely ground flour into a jar filled with hot water (photo 1 below). This could take about a week. You can taste it, and when the nut meal tastes good to you, you can use them. Replace the water when it turns brown. If you have the option, place the jar in a refrigerator because if it is hot out it can begin to ferment.

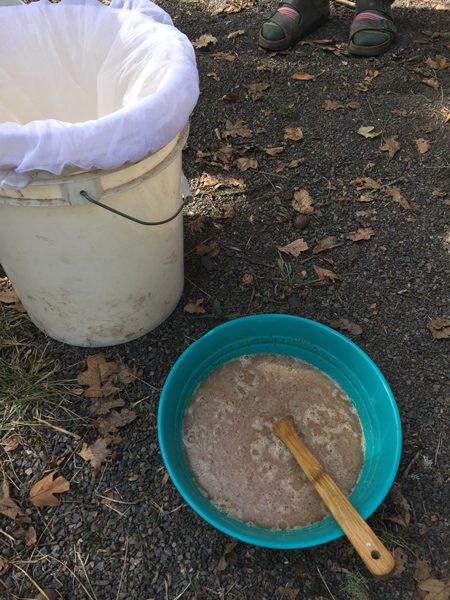

The second way was to put the flour into a bowl, pour water over it to cover and stir, then pour the whole thing through a mesh bag that you can get at a homebrew store (photo 2 below). Pour more water over the flour until it tastes good. You can “hot leach” the acorns by simmering them over a flame or on a woodstove. It can take over a day to leach whole nuts this way.

Our instructor had some already leached flour that we cooked with a little water into “mush.” One cup of flour will expand to about 3 cups of “mush.” The taste was good. It was nutty, but bland. The flavor really woke up when I put some salt on it. If you have any toppings like butter, onions, or salt and pepper, that would make the mush taste much better. But even with no flavorings at all, it was edible and even good, just bland.

Our instructor also had some already-prepared chili that she had made using whole acorns cooked in place of beans. The other ingredients were the same as what you would normally put into chili. The flavor of the chili was great, it was just odd because the nuts oxidized and turned the whole jar of chili a dark, inky black color. If you just focus on the taste and not the color, that too was good! The flour could be made into bread or pasta just as you would use any other flour.

One caution I have is that people can apparently be sensitive to acorns. My partner is allergic to pecans and walnuts, and when he ate the mush, he said it made his tongue feel fuzzy the same way that other nuts do that he can’t eat. So he’s not into using acorns as a survival food because of this. If anyone in your family does have a tree nut sensitivity, you might test it out and see if they can safely eat acorns before you plan for that to be a source of sustenance.

Bottom line…I will collect acorns now whenever I have a chance to. Do your research, read your books and watch your videos. But if you get a chance to learn from an expert, do it. It’s the best way to really master a survival skill.

I took my acorn workshop through Columbines School of Botanical Studies.